Olivia Ikey

Inuit Studies Conference (2022)

"We have moss, swamp and rock. My family in Salluit, they’re on rock and they’re in a valley. We have stilted houses on top of the ground, we don’t have underground water pipes, we get water delivered."

There are many ways of tying a building to its site in the village or elsewhere. The Inuit home is both an extension and an expression of Nuna, its interior and exterior spaces linking daily activities to the community and to the land.

A lot can be learned from the way self-built family cabins and camps have continuously related to the land. From a practical and traditional standpoint, the location of cabins generally takes into account access to and space for activities, construction on solid and dry ground (like rock outcrops), views oriented toward the waterways (looking out for food and visitors), minimal exposition to strong winds, and seasonal considerations to locate the door. Inuit have long stressed the importance of houses being oriented to offer a view of the bay or the river, not only for the beauty of the landscape but also to monitor hunting and fishing activities.

What We've Learned

Realities

Paths for Change

The wise siting of buildings in the village may borrow from these connections that link practices to seasons and to Nuna. In a variety of contexts, whether sites are pads or bedrock, flat or sloped, siting is a culturally informed decision that takes into account various relationships to the ground, topography, seasonal sun and wind trajectories, proximities, and views of the land.

Wise siting eventually translates to Inuit aspirations of being able to choose a site for their own homes and of preserving natural soils nearby and within the village.

Calls to Action

29. Follow the elements

Position the house and windows to maximize sunlight and passive heating.

Place the house entrance on a side opposite to dominant winds.

Make use of land attributes to enhance a sense of security against the elements (stable soil above flood levels, natural wind deflectors, etc.).

Take advantage of the topography and solid ground to anchor buildings on rock outcrops without the use of pads. (See Relation to Ground key)

30. Offer enjoyable views

Orient the house and windows to avoid facing neighbours in “face to face” situations.

Offer views of meaningful places and the land, in line with Nuna cabin life.

31. Make room for storage around the house

Include sheds and exterior spaces to store vehicles and other belongings.

Consider the various meanings and practicalities attached to storage (regarding food conservation, for example).

32. Reserve outdoor space for activities

Include enough protected space near the house to do traditional activities in all seasons: tents, smoking and drying structures, fire or barbecue pits, etc.

The cabins of Nunavik mark the evolution of the Inuit way of life. They reveal a know-how with rich potential for contemporary Northern housing.

Composed of objects and materials that are mostly recycled, diverted, or randomly acquired, cabins are ingeniously and resiliently located on the tundra. A better knowledge of cabins will enhance local know-how and contributing to culturally appropriate solutions for built environments.

What defines the tundra camps and cabins? What lessons do they teach about the ways of living in the North?

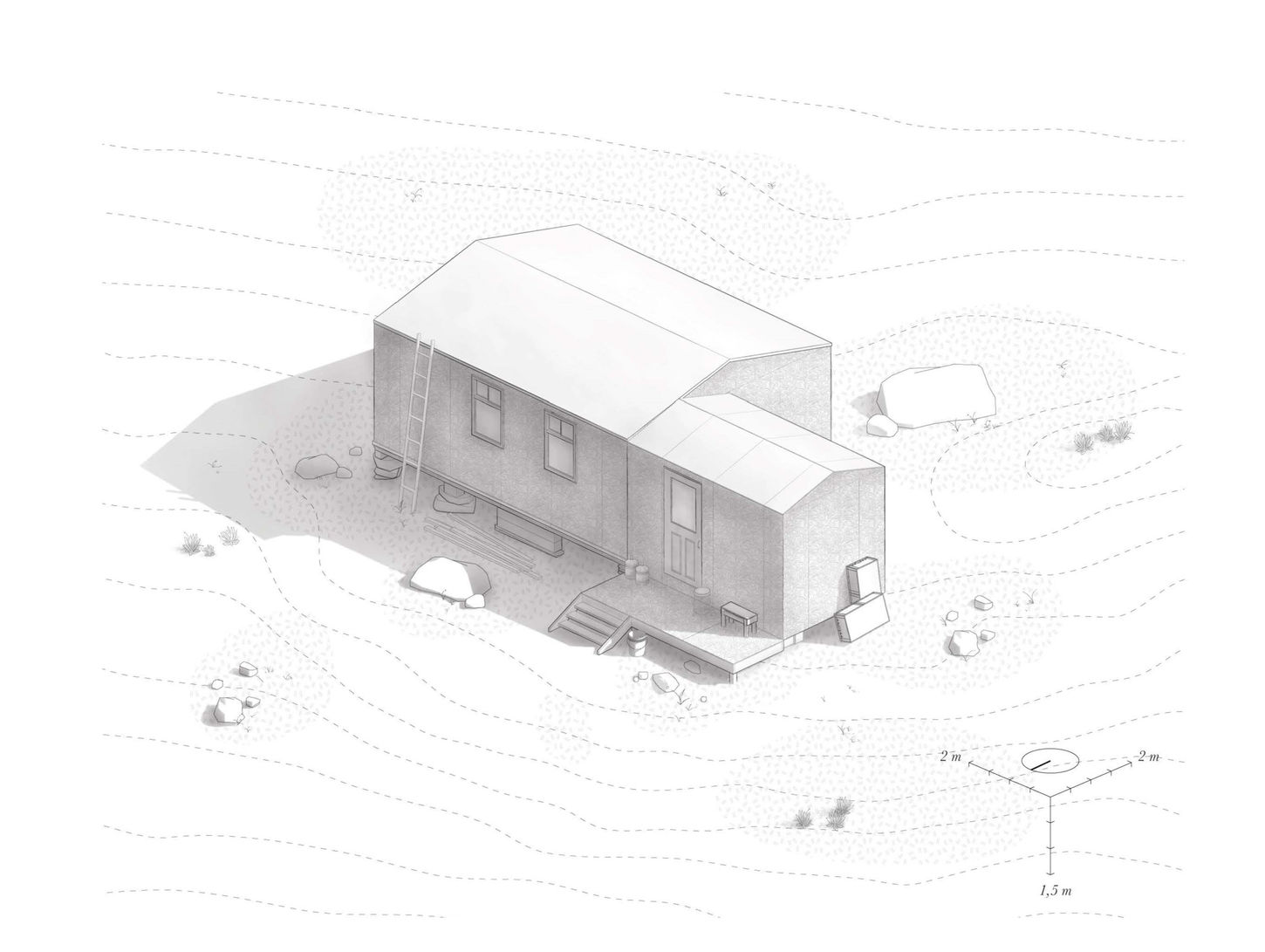

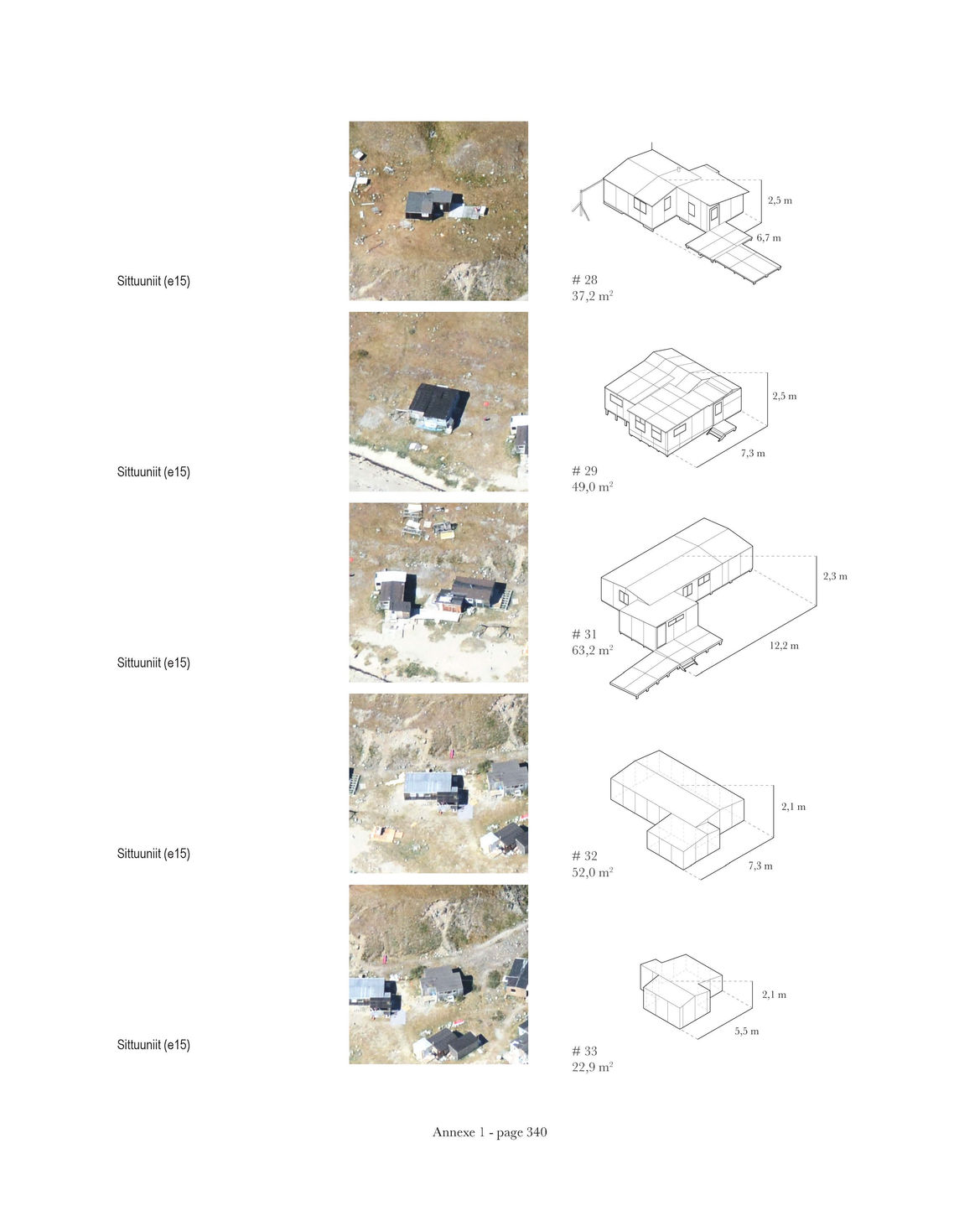

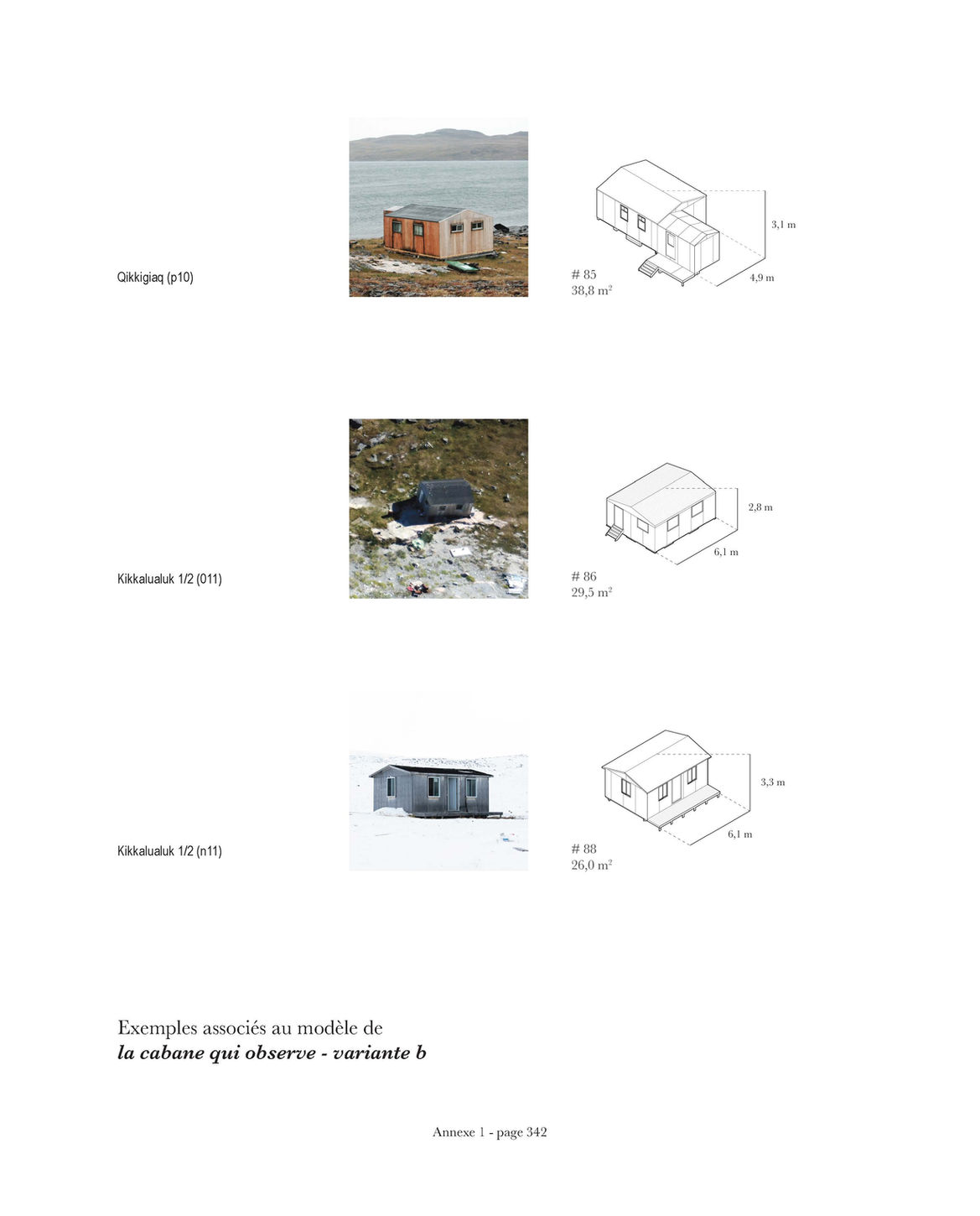

This research project uses interviews with self-builders and in situ observations of cabins along the Salluit Fjord to gain knowledge on the conceptual and constructive processes taking place on the land. A graphic “deconstruction” exercise reveals the components, layer by layer, highlighting the simplicity of construction and depicting ways of anchoring to the land through strategic groupings (security, camp relations) and maximized views of the river or mountains (kayaks, caribou, changing weather). This detailed understanding of the fabrication, occupation, and transformation of cabins and camps translates Inuit connections to the land.

Cabins are the cultural expression of these relationships that are continuously renewed and remain important aspects of Inuit dwelling to consider when addressing architecture and planning in the North.

By P.-O. Demeule, research thesis, École d’architecture de l’Université Laval, 2021

Cabins and Camps: Know-How and Self-Building on the Tundra

Innovations: Thinking Outside the Box

References

Open Access

Blouin, M (2020) La recherche d’un équilibre. Le village et la reconnexion avec le territoire, Revue ARQ Architecture and design Québec, 190 : 16-17. https://issuu.com/hlnq.linq/docs/arq190-habiterlenord

Demeule, P-O (2021) Cabanes et campements du fjord de Salluit : une lecture des savoir-faire locaux et des pratiques d'autoconstruction dans la toundra. Mémoire de maitrise, Université Laval. URI : http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11794/71108

Demeule, P-O (2020) Savoir-faire locaux et auto-construction dans la toundra. une lecture des cabanes du fjord de salluit (note de recherche). Études Inuit Studies, 44(1-2), 109–159. https://doi.org/10.7202/1081800ar

Demeule, P-O (2020) Learning from cabins. Video presentation. Habiter le Nord québécois, U. Laval, Québec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zyHAdt3shpE

Gauthier, S (2020) ABC des sols gelés. Présentation vidéo. Habiter le Nord québécois, U. Laval, Québec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f1hLp16cjk0&

Other

Zrudlo, L (2001) A search for cultural and contextual identity in contemporary Arctic architecture. Polar Record, 37(200), 55-66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247400026759